Handmade Portraits: The Sword Maker from Etsy on Vimeo.

Since I am currently studying welding and taking a class on metallurgy I feel this is not only interesting but appropriate.

This sword maker is using a process (described below) that is becoming more and more rare. Though the steel he is producing is still widely available (Damascus steel) it is hardly made like this any more.

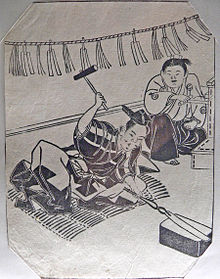

The forging of a Japanese blade typically took many days or weeks, several artists were involved. There was a smith to forge the rough shape, often a second smith (apprentice) to fold the metal, a specialist polisher, and even a specialist for the edge itself. Often, there were sheath, hilt, and tsuba specialists as well.

Forging

In traditional Japanese sword making, the low carbon steel is folded several times by itself, to purify it. This produces the soft metal, called shingane, to be used for the core of the blade. The high carbon "tamahagane" and the higher carbon nabe-gane are then forged in alternating layers. The nabe-gane is heated, quenched in water, and then broken into small pieces to help free it from slag. Slag is the excess metal that sticks and is usually very porous which makes it low quality. The tamahagane is then forged into a single plate, and the pieces of nabe-gane are piled on top, and the whole thing is forge welded into a single block, which is called the age-kitae process. The block is then elongated, cut, folded, and forge welded again. The steel can be folded transversely, (from front to back), or longitudinally, (from side to side). Often both folding directions are used to produce the desired grain pattern. This process, called the shita-kitae, is repeated from 8 to as many as 16 times. After 20 foldings, (220, or about a million individual layers), there is too much diffusion in the carbon content, the steel becomes almost homogenous in this respect, and the act of folding no longer gives any benefit to the steel. Depending on the amount of carbon introduced, this process forms either the very hard steel for the edge, called hagane, or the slightly less hardenable spring steel, called kawagane, which is often used for the sides and the back. The best known part of the manufacturing process is the folding of the steel, where the swords are made by repeatedly heating, hammering and folding the metal. The technique of repeated heating and folding of steel for swords was found in many other cultures and did not necessarily have one single point of origin.

During the last few foldings, the steel may be forged into several thin plates, stacked, and forge welded into a brick. The grain of the steel is carefully positioned between adjacent layers, with the exact configuration dependent on the part of the blade for which the steel will be used. Between each heating and folding, the steel is coated in a mixture of clay, water and straw-ash to protect it from oxidation and carburization. The clay, in turn, acts as a flux, pulling impurities out from between the layers. This practice became popular due to the use of highly impure metals, stemming from the low temperature yielded in the smelting at that time and place. The folding did several things:

- It provided alternating layers of differing hardenability. During quenching, the high carbon layers achieve greater hardness than the medium carbon layers. The hardness of the high carbon steels combine with the ductility of the low carbon steels to form the property of toughness.

- It eliminated any voids in the metal.

- It homogenized the metal, spreading the elements (such as carbon) evenly throughout - increasing the effective strength by decreasing the number of potential weak points.

- It burned off many impurities, helping to overcome the poor quality of the raw Japanese steel.

- It created up to 65000 layers, by continuously decarburizing the surface and bringing it into the blade's interior, which gives the swords their grain (for comparison see pattern welding).

Generally, swords were created with the grain of the blade (called hada) running down the blade like the grain on a plank of wood. Straight grains were called masame-hada, wood-like grain itame, wood-burl grain mokume, and concentric wavy grain (an uncommon feature seen almost exclusively in the Gassan school) ayasugi-hada. The difference between the first three grains is that of cutting a tree along the grain, at an angle, and perpendicular to its direction of growth (mokume-gane) respectively, the angle causing the "stretched" pattern. The blades that were considered the most robust, reliable, and of highest quality were those made in the Mino tradition, especially those of Magoroku Kanemoto. Bizen tradition, which specialized in mokume, and some schools of Yamato tradition were also considered strong warrior's weapons.

Assembly

In addition to folding the steel, high quality Japanese swords are also composed of various distinct sections of different types of steel. Known in China as bao gang 包钢 (literally "wrapped steel") since at least the Tang Dynasty, this manufacturing technique uses different types of steel in different parts of the sword to accentuate the desired characteristics in various parts of the sword beyond the level offered by differentiated tempering.

The vast majority of modern katana and wakizashi are the maru (sometimes also called muku) type which is the most basic, with the entire sword being composed of one single steel. The kobuse type is made using two steels, which are called hagane (edge steel) and shingane (core steel). Honsanmai and shihozume types add the third steel, called kawagane (skin steel). There are almost an infinite number of ways the steel could be assembled, which often varied considerably from smith to smith. Sometimes the hagane is "drawn out," (hammered into a bar), bent into a 'U' shaped trough, and the very soft shingane is inserted into the harder piece. Then they are forge welded together and hammered into the basic shape of the sword. By the end of the process, the two pieces of steel are fused together, but retain their differences in hardenability. The more complex types of construction are typically only found in antique weapons, with the vast majority of modern weapons being composed of a single section, or at most two or three sections.

Another way is to assemble the different pieces into a block, forge weld it together, and then draw out the steel into a sword so that the correct steel ends up in the desired place. This method is often used for the complex models, which allow for parrying without fear of damaging the side of the blade. To make honsanmai or shihozume types, pieces of hard steel are added to the outside of the blade in a similar fashion. The shihozume and soshu types are quite rare, but added a rear support.

Geometry (shape and form)

As Japan entered the Bronze Age, the swords found in Japan were very similar in shape to those found in continental Asia, i.e., China or Korea, and the Japanese adopted the Chinese convention for sword terminology along with metallurgy and swordmaking technology, classifying swords into the (either straight or curved) single-edged variety called tou 刀 and the (straight) double-edged variety called ken 剣. There is some small overlap in that there were some double-edged curved swords such as Tulwars or Scimitars which were called Tou, because the curvature meant that the "front" edge was used in the overwhelming majority of instances.

Over time, however, the single-edged sword with its characteristic curvature became so dominant a style in Japan that tou and ken came to be used interchangeably to refer to swords in Japan and by others to refer to Japanese swords. For example, the Japanese typically refer to Japanese swords as 日本刀 nihontou ("Japanese tou" i.e. "Japanese (single-edged) sword"), while the character ken 剣 is used in such terms as kendo and kenjutsu. Modern formal usage often uses both characters in referring to a collection of swords, for example, in naming the The Japanese Sword Museum.

The prototype of the Japanese sword was the chokuto 直刀, or "straight (single-edged) sword", a design that can be fairly described as a Japanese sword without any curvature, with a handle that is usually only a few inches long and therefore suitable for single-handed use only, with a sword guard that is prominent only on the front (where the edge is pointed) and back sides and sometimes only on the front side of the sword blade, and with a ring pommel. This design was moderately common in China and Korea during the Warring States and Han Dynasties, fading from popularity and disappearing during the Tang Dynasty. A number of such swords have been excavated in Japan from graves dating back to the kofun period.

As the chokuto evolved into the Japanese sword as it is known today, it acquired its characteristic curvature and Japanese style fittings, including the long handle making it suitable for either one-handed or two-handed use, the non-protruding pommel, and a tsuba sword guard that protruded from the sword in all directions, i.e., that is not a cross piece or a guard for the edge or edge and back sides of the blade only but a guard intended to protect the hand on all sides of the blade. The shape of the Japanese tsuba evolved in parallel with Japanese swordsmithing and Japanese swordsmanship. As Japanese swordsmiths acquired the ability to achieve an extremely hard edge, Japanese swordsmanship evolved to protect the edge against chipping, notching, and breakage by parrying with the sides or backs of swords, avoiding edge-to-edge contact. This in turn resulted in the need to protect the sword hand from a sliding blade in parries on the sides and backs, i.e., parts of the blade other than the edge side, forming the rationale behind the Japanese styled tsuba, which protrudes from the blade in every direction.

This style of parrying in Japanese swordsmanship has also resulted in some antique swords that have actually been used in battle, exhibiting notches on the sides or backs of blades.

Heat treating

Having a single edge also has certain advantages, one of the most important being that the entire rest of the sword can be used to reinforce and support the edge, and the Japanese style of sword making takes full advantage of this. When finished, the steel is not quenched or tempered in the conventional European fashion i.e. uniformly throughout the blade. Steel’s exact flex and strength vary dramatically with heat treating. If steel cools quickly it becomes martensite, which is very hard but brittle. Slower and it becomes pearlite, which bends easily and does not hold an edge. To maximize both the cutting edge and the resilience of the sword spine, the technique of differentiated tempering, first found in China during the first century BC, is used: the sword is heated and painted with layers of clay—the mixture being closely guarded trade secrets of the various smiths, but generally containing clay and coal ash as the primary ingredients—with a thin layer or none at all on the edge of the sword ensuring quick cooling to maximize the hardening for the edge, while a thicker layer of clay on the rest of the blade causing slower cooling and softer, more resilient steel to allow the blade to absorb shock without breaking.

This process also has two side effects that have come to characterize Japanese swords—first, it makes the edge of the blade, which cools quickly and forms evenly dispersed cementite particles embedded within a ferrite matrix (typical oftempered martensite), which will actually cause the edge part of the blade to expand while the sword spine remains hot and pliable for several seconds, which aids the smith in establishing the curvature of the blade. Second, the differentiated heat treatment and the materials with which the steel comes into contact creates different coloration in the steel, resulting in the Hamon 刃紋 (frequently translated as "tempering line" but really better translated as "tempering pattern"), that is used as a factor to judge both the quality and beauty of the finished blade. The differentiated Hamon patterns resulting from the manner in which the clay is applied can also act as an indicator of the style of sword making, and sometimes also as a signature for the individual smith.

Decoration

Almost all blades are decorated, although not all blades are decorated on the visible part of the blade. Once the blade is cool, and the mud is scraped off, the blade has designs and grooves cut into it. One of the most important markings on the sword is performed here: the file markings. These are cut into the tang, or the hilt-section of the blade, where they will be covered by a hilt later. The tang is never supposed to be cleaned: doing this can cut the value of the sword in half or more. The purpose is to show how well the blade steel ages. A number of different types of file markings are used, including horizontal, slanted, and checked, known as ichi-monji, ko-sujikai, sujikai, ō-sujikai, katte-agari, shinogi-kiri-sujikai, taka-no-ha, and gyaku-taka-no-ha. A grid of marks, from raking the file diagonally both ways across the tang, is called higaki, whereas specialized "full dress" file marks are called kesho-yasuri. Lastly, if the blade is very old, it may have been shaved instead of filed. This is called sensuki. While ornamental, these file marks also serve the purpose of providing an uneven surface which bites well into the tsuka, or the hilt which fits over it and is made from wood. It is this pressure fit for the most part that holds the tsuka in place during the strike, while the mekugi pin serves as a secondary method and a safety.

Some other marks on the blade are aesthetic: signatures and dedications written in kanji and engravings depicting gods, dragons, or other acceptable beings, called horimono. Some are more practical. The presence of a so-called "blood groove" or fuller does not in actuality allow blood to flow more freely from cuts made with the sword. Fullers neither have a demonstrable difference in the ease of withdrawing a blade nor do they reduce the sucking sound that many people believe was the reason for including such a feature in commando knives in World War II.[12] The grooves are analogous in structure to an I beam, lessening the weight of the sword yet keeping structural integrity and strength.[12] Grooves come in wide (bo-hi), twin narrow (futasuji-hi), twin wide and narrow (bo-hi ni tsure-hi), short (koshi-hi), twin short (gomabushi), twin long with joined tips (shobu-hi), twin long with irregular breaks (kuichigai-hi), and halberd-style (naginata-hi).

Furthermore the grooves (always done on both sides of the blade) make a whistling sound when the sword is swung (the tachikaze太刀風). If the swordsman hears one whistle when swinging a grooved katana then that means that just one groove is making the whistle. Two whistles means that both the edge of the blade and a groove are making a whistle, and three whistles together (the blade edge and both grooves) would tell the swordsman that his blade is perfectly angled with the direction of the cut.

Polishing

When the rough blade is completed, the swordsmith turns the blade over to a polisher called a togishi, whose job it is to refine the shape of a blade and improve its aesthetic value. The entire process takes considerable time, in some cases easily up to several weeks. Early polishers used three types of stone, whereas a modern polisher generally uses seven. The modern high level of polish was not normally done before around 1600, since greater emphasis was placed on function over form. The polishing process almost always takes longer than even crafting, and a good polish can greatly improve the beauty of a blade, while a bad one can ruin the best of blades. More importantly, inexperienced polishers can permanently ruin a blade by badly disrupting its geometry or wearing down too much steel, both of which effectively destroy the sword's monetary, historic, artistic, and functional value.

Modern swordsmithing

Traditional swords are still made in Japan and occasionally elsewhere; they are termed "shinsakuto" or "shinken" (true sword), and can be very expensive. These are not considered reproductions as they are made by traditional techniques and from traditional materials. Swordsmiths in Japan are licensed; acquiring this license requires a long apprenticeship. Outside of Japan there are a couple of smiths working by traditional or mostly-traditional techniques, and occasional short courses taught in Japanese swordsmithing. The only two Japanese-licensed smiths outside of Japan are, Keith Austin (art-name Nobuhira or Nobuyoshi) died in 1997, and 17th Generation Yoshimoto Bladesmith Murray Carter.

A very large number of low-quality reproduction katana and wakizashi are available; their prices usually range between $10 to about $200. These cheap blades are Japanese in shape only—they are usually machine made and machine sharpened, and minimally hardened or heat-treated. The hamon pattern (if any) on the blade is applied by scuffing, etching or otherwise marking the surface, without any difference in hardness or temper of the edge. The metal used to make low-quality blades is mostly cheap stainless steel, and typically is much harder and more brittle than true katana. Finally, cheap reproduction Japanese swords usually have fancy designs on them since they are just for show. Better-quality reproduction katana typically range from $200 to about $1000 (though some can go easily above two thousand for quality production blades, folded and often traditionally constructed and with a proper polish), and high-quality or custom-made reproductions can go up to $15000-$50000. These blades are made to be used for cutting, and are usually heat-treated. High-quality reproductions made from carbon steel will often have a differential hardness or temper similar to traditionally-made swords, and will show a hamon; they won't show a hada (grain), since they're not often made from folded steel.

A wide range of steels are used in reproductions, ranging from carbon steels such as 1020, 1040, 1060, 1070, 1095, and 5160, stainless steels such as 400, 420, 440, to high-end specialty steels such as L6 and D2. Most cheap reproductions are made from inexpensive stainless steels such as 440A (often just termed "440"). With a normal Rockwell hardness of 56 and up to 60, stainless steel is much harder than the back of a differentially hardened katana, (HR50), and is therefore much more prone to breaking, especially when used to make long blades. Stainless steel is also much softer at the edge (a traditional katana is usually more than HR60 at the edge). Furthermore, cheap swords designed as wall-hanging or sword rack decorations often also have a "rat-tail" tang, which is a thin, usually threaded bolt of metal welded onto the blade at the hilt area. These are a major weak point and often break at the weld, resulting in an extremely dangerous and unreliable sword.

Some modern swordsmiths have made high quality reproduction swords using the traditional method, including one Japanese swordsmith who began manufacturing swords in Thailand using traditional methods, and various American and Chinese manufacturers. These however will always be different from Japanese swords made in Japan, as it is illegal to export the Tamahagane jewel steel as such without it having been made into value-added products first. Nevertheless, some manufacturers have made differentially tempered swords folded in the traditional method available for relatively little money (often one to three thousand dollars), and differentially tempered, non-folded steel swords for several hundred. Some practicing martial artists prefer modern swords, whether of this type or made in Japan by Japanese craftsmen, because many of them cater to martial arts demonstrations by designing "extra light" swords which can be maneuvered relatively faster for longer periods of time, or swords specifically designed to perform well at cutting practice targets, with thinner blades and either razor-like flat-ground edges or even a hollow ground edges.

Commercial folded steel swords

In recent years, as the public has become more aware of the Japanese style of sword making, many companies have begun to offer folded steel swords, typically marketing them as "damascus" swords, which usually command higher prices than their non-folded equivalents. Many people are willing to pay a premium for such blades in the belief that any folded blade will be superior in performance and quality to any non-folded blade, but in fact it is just the reverse—a low quality folded sword is actually much more likely to contain metallurgical flaws than a sword made from a single piece of steel that came off the line in a modern steel plant, and any flaws would significantly increase the likelihood of breakage at the moment of contact. Add to this the lack of differentiated heat treatment, which already renders the blade brittle compared to a traditional Japanese sword or even a Western-style sword (which would typically not be tempered to as high a hardness due to expectations of striking metal armor), and the result is a sword that would be much more likely to break or shatter at the moment of contact, even for demonstration or "test" cutting, making the use of such a sword potentially highly hazardous to the wielder and any bystanders, as any breakage at the moment of contact will result in sharpened metal flying at unpredictable directions with the force of the blow.

Sword manufacturers marketing such low end folded swords tend to choose softer steels such as 1020 or 400 for this purpose, since they are easier to work and fold, and will also often attempt to enhance the appearance of the folding layers by making comparatively few folds (thus leaving thicker folds), folding soft iron with steel, folding stainless steel with non-stainless steel, using an acid wash to blacken the folds that are less corrosion resistant, or some combination of these techniques, resulting in a blade with extremely prominent folding marks. Where the acid wash technique is used, the blade will be various shades of gray and black. and frequently exhibit no hamon tempering line. All swords made by the traditional Japanese method, regardless of the quality or assembly type, results in a bright and shiny blade upon completion, and therefore any blade that is black or gray in color when new absolutely cannot have been made in the traditional manner of the Japanese swordsmiths.

Commercial folded steel swords can also made by stamping. In this method, steel is heated and folded in a sheet large enough to make multiple swords from, and then cut or "stamped" into long "blanks" somewhat resembling the shape of the blade. The blanks are then ground down to form the edges, exposing the folds. Due the comparative ease of manufacturing and greater efficiency (in the sense that less of the sheet tends to be lost during the stamping process), this method is most commonly seen in the manufacture of straight "damascus steel" swords such as sword canes and what are often called "double-edged samurai swords" but which are really just Chinese-style ken swords with Japanese-style fittings. The physical act of the stamping alters the molecular structure at the location of the cut, which can cause deterioration in the quality of the steel in subtle ways. While it is possible to adjust for this by simply grinding down the edges further and removing the portion of the blade that has had its molecular structure thus disturbed, it is doubtful that a manufacturer that has sought to reduce cost and production time by stamping folded sheet steel would then go through such additional efforts and costs to improve the quality of the blade. In any case, even if the stamped edge is ground away, what one is left with is still a low quality blade.

Regardless of the price or the production method of the sword, it is worthwhile to remember that the choice of materials and manufacturing techniques based on the desired appearance, rather than the performance of the resulting product will predictably result in swords which are serviceable for display only in the vast majority of instances.

Replica swords, varying and copying the major styles, have an active market world-wide. Replicas usually do not have a sharp blade but the point is quite and easily used as a stabbing weapon. Replicas sell to tourists in Tokyo for about $100 to $250 USD. Export is no problem, but some nations limit imports even of replicas.

No comments:

Post a Comment